How the barbarian invasions shaped the modern world : The Vikings, Vandals, Huns, Mongols, Goths,

and Tartars who razed the old world and formed the new / Thomas J. Craughwell.

844 - 851 AD

THE RESURRECTION

OF HASTEIN:

THE VIKINGS IN THE

MEDITERRANEAN

AT THE BATTLE OF

TOURS IN 732, T H E

FRANKISH WARLORD,

CHARLES MARTEL,

DEFEATED T H E MOORS

AND SAVED WESTERN

EUROPE FROM

MOORISH CONQUEST.

THE MEDITERRANEAN SEA WAS THE ONE PLACE IN EUROPE

the Vikings learned to avoid. Unlike England, Ireland, northern

France, and the Ukraine, there was a power along the inland sea the

Vikings could neither frighten nor defeat. That power was the Moors.

Concentrated along northern Africa and in Spain and Portugal, the

Moorish empire possessed a war machine that made Europe and Byzantium

nervous. The Moors had invaded the Iberian Peninsula from present-day

Morocco in 711 and within eight years had conquered Spain and Portugal (in

contrast, it would take the Spanish and the Portuguese 700 years to get their

countries back).

In 732, the Moors thundered across the Pyrenees into France. They got as

far as Tour, about 150 miles south of Paris, when they were turned back in an

epic battle against the Franks, led by Charles Martel, "the hero of the age," as

the historian Edward Gibbon called him. The de facto ruler at a time when

the Frankish kings had become very weak, Charles was also a skillful

commander who had already enjoyed victories over at least four different

Germanic nations before he fought the Moors. By crushing the army of Emir

Abdul Rahman (who was killed in the battle) and driving the survivors back

across the Pyrenees, Charles saved western Europe from Moorish conquest.

South of the Pyrenees, the Moors were still a major military power. The

Vikings they regarded as a nuisance, but a destructive, disruptive one that

could not be ignored. That is why, in the wake of Hastein and Bjorn's raids on

southern Spain in 859, the emir of Cordoba built the first Moorish fleet to

fight and beat the Vikings on their own turf. One crushing loss to the Moorish

navy was all it took for the Vikings to learn their lesson: The surviving dragon

ships limped northward, never to return to the Mediterranean.

T I M E L I N E

7 1 1 - 7 2 2 : THE MOORS,

MUSLIM INVADERS FROM NORTH

AFRICA, CONQUER ALMOST ALL OF

SPAIN A N D PORTUGAL.

844: THIRTY BOATLOADS OF

VIKINGS ATTACK A N D CONQUER

SEVILLE IN SOUTHERN SPAIN.

THEY PLUNDER THE SURROUNDING

COUNTRYSIDE UNTILTHE MOORS

DRIVE T H EM OUT.

c. 849: TWELVE-YEAR-OLD

BJORN, A DANISH PRINCE, IS SENT

TO LIVE WITH HASTEIN TO LEARN

HOW TO BE A VIKING RAIDER AND

WARRIOR.

SUMMER 859:

IN NORTH AFRICA, HASTEIN AND

BJORN TAKE CAPTIVES TO BE SOLD

IN THE SLAVE MARKETS OF

IRELAND.

WINTER

859-860: FROM

THEIR WINTER QUARTERS ON

THE FRENCH RIVIERA, THE

TWO VIKING CHIEFS LEAD

SUCCESSFUL ATTACKS ON THE

FRENCH CITIES OF NIMES,

ARLES, AND VALENCE, AS

WELL AS PISA IN ITALY.

860: HASTEIN AND

BJORN RAID T H E ITALIAN

TOWN OF LUNA, MISTAKING

IT FOR ROME.

861 : T H E VIKINGS SAIL

FOR HOME BUT FIND THEIR

WAY BLOCKED AT T H E

STRAIT OF GIBRALTAR BY

A MOORISH FLEET. ONLY

TWENTY VIKING SHIPS

MAKE IT THROUGH T H E

BLOCKADE.

c. 965-971:

THE VIKINGS OCCUPY

GALICIA IN NORTHWEST

SPAIN UNTIL A SPANISH

ARMY COMMANDED BY

COUNT GONSALVO SANCHO

DRIVES THEM OUT.

C. 950-1204:

THOUSANDS OF

VIKINGS TRAVELTO

CONSTANTINOPLE TO

ENLIST AS MERCENARIES

IN T H E BYZANTINE ARMY.

Charles Martel saved western Europe from the Moors, and the Moors

saved the Mediterranean world from the Vikings.

A M O R A L D I L E M M A

The men on the battlements could scarcely believe what they were hearing. In

front of the main gates of the city lay a man on a litter, surrounded by a small

band of Vikings. "Open the gates!" their spokesman shouted. "Our lord is very

ill and wants to be baptized before he dies."

Earlier that same day in 859, when sixty two dragon-prowed ships sailed

into the harbor of Luna on the western coast of Italy, the alarm bells had rung,

the people in the suburbs had raced for the safety of the city, and the garrison

had barred the gates and taken their posts on the walls, bracing themselves for

a Viking attack. Instead of an assault, however, they were faced with a moral

dilemma: As Christians, could they turn away a dying man who asked for

salvation? So the soldiers sent their own messengers to the count who ruled the

city and the bishop to let them decide what was to be done. Meanwhile, the

Vikings waited patiently at the city gates.

After a quick conference, the count and the bishop agreed to admit the

Vikings. They sent a guard of soldiers to escort them to the cathedral, where

the bishop baptized the sick man—his named was Hastein—and the count

served as his godfather. Throughout the ceremony, Hastein's attendants

remained quiet, solemn, and respectful. As for Hastein, he feigned a mix of

piety and weakness. When the baptismal rite was concluded, the Vikings

lifted the litter and bore their newly christened lord back through the town

and out to his ship. Once the Vikings were gone, the guards barred the gates

again—just to be on the safe side.

"A L E W D , U N B R I D L E D , C O N T E N T I O U S R A S C A L "

Details about Hastein's life are hard to come by. He was probably a Swede. He

must have been an experienced, respected Viking leader otherwise he never

could have raised a fleet of 62 longships in 859 for a raiding voyage into the

Mediterranean. A typical longship held between thirty and forty men, which

would have place Hastein in command of about 2,400 Vikings. William of

Jumieges, a Norman monk and historian, described the scene:

On the appointed day, the ships were pushed into the sea and the

soldiers hastened to go aboard. They raised the standards, spread the

sails before the wind, and like agile wolves set out to rend the Lord's

sheep, pouring out human blood to their god Thor.

We do not know what Hastein looked like, but another Norman monk and

historian, Dudo of Saint-Quentin, writing more than one hundred years after

the fact, left us an assessment of his character. Dudo described Hastein as

"accursed and headstrong, extremely cruel and harsh, destructive,

troublesome, wild, ferocious, infamous, destructive and inconstant, brash,

conceited and lawless, death-dealing, rude, everywhere on guard, a rebellious

traitor and kindler of evil, a double-faced hypocrite, an ungodly, arrogant,

seductive and foolhardy deceiver, a lewd, unbridled, contentious rascal."

Dudo was not exaggerating. Hastein's raids in northern France had been

so destructive that King Charles the Bald bought him off by handing over to

Hastein the city of Chartres. The Viking chief had no use for a town, so he

sold it to a Frankish count named Theobald. In Brittany, Hastein made a more

practical peace treaty with Count Salomon, promising to cease all raids on the

province in exchange for a payment of 500 cows.

About ten years before the voyage to the Mediterranean, Ragnar Lodbrok,

the king of Sweden and Denmark, had placed his son twelve-year-old son

Bjorn in Hastein's care, instructing him to teach the boy how be a proper

Viking warrior. Bjorn became Hastein's most trusted lieutenant and joined

him on the Mediterranean raid. By then he had acquired a nickname—Bjorn

Ironside, because, the Vikings said, his mother Aslaug had cast a spell that

made the young man invulnerable on the battlefield.

THE V I K I N G R A I D I N T H E M E D I T E R R A N E A N

After days of digging beneath Seville's walls, a handful of Vikings set fire to the

wooden beams that held up the tunnel, and then sprinted outside to watch the

result. The burned beams gave way, the tunnel collapsed, and with a thunderous

crash, a section of Seville's defensive walls fell and 1,000 battle-crazed

Viking warriors surged into the city. Moorish soldiers who had manned the

walls now retreated at a full run to the citadel, the only refuge within Seville

strong enough to withstand the Vikings.

Unable to breach the citadel walls, the Vikings gave up the attempt and set

about looting the city. They took their time, spending a week amassing treasures

from the palaces of the Moorish aristocracy and the houses of the city's

wealthy silk merchants. They rounded up the strongest and most attractive men

and women of Seville—Moors and Christians—for future sale to slavers and

herded the weeping throng down to their ships on the Guadalquivir River.

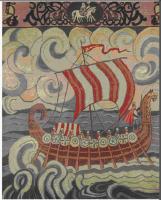

HASTEIN LED INTO

THE MEDITERRANEAN

A FLEET OF SIXTY TWO

VIKING LONG SHIPS

SIMILAR TO T H I S ONE,

DEPICTED IN A

TWENTIETH-CENTURY

TAPESTRY.

The year was 844. In preparation for their first raid on Spain, the Vikings

had beached their fleet of thirty ships on Isla Menor at the mouth of Spain's

Guadalquivir River. From their base camp on the island, the Northmen

attacked Seville, where the plunder proved to be so rich the majority of

Vikings established a branch operation in the ransacked city, riding out on

horseback to raid the surrounding towns and shipping their spoils and captives

down to Isla Menor. For six weeks, the Vikings lingered in the battered city,

giving the Moors ample time to regroup and launch a counter-offensive.

The Moors called the Vikings "Majus," derived from the Persian word

"magus" for a priest of the Zoroastrian religion, a sect renowned for fireworship.

Magus also is the source for the English words "magi," "magic," and

"magician," but among the Moors Majus meant "heathen."

As the Vikings took their time stripping the countryside around Seville,

Abdurrhaman II, emir of Cordoba, gathered his army. He sent small units to

ambush Viking raiding parties, while he led the main force to Seville where he

took the Vikings by surprise. He captured 500 Vikings, so many that there was

no room to hang them all on the city gallows; to accommodate the overflow,

the Moors strung up Vikings from palm trees.

To celebrate his triumph (and perhaps to intimidate the recipient)

Abdurrhaman sent 200 Vikings heads to a friend and ally in Tangiers.

Meanwhile, the Vikings, who escaped the Moors' counterattack, were

surrounded and stranded on Isla Menor, where they and their captives were

starving. They sent a message to the emir with an offer: The Vikings would

release all their captives in exchange for a guarantee of safe passage out of

Spain, as well as a quantity of food and fresh clothes. Abdurrhaman paid the

"ransom," taking great pleasure in seeing the Vikings depart and having his

captive people returned to him.

The first Viking incursion into the Mediterranean had ended badly, but

word spread among the Northmen of the wealth of the towns, the abundance

of food and wine, the fruit and livestock in the countryside, and the warm

climate, all of which made the region irresistible to other Vikings. Fifteen

years later, Hastein and Bjorn took what they considered to be a virtually

invincible fleet of 62 long ships into the Mediterranean to plunder the

southern paradise.

AT T H E CONCLUSION

OF HIS "FUNERAL,"

HASTEIN LEAPT OFF T H E

BIER A N D WITH HIS

VIKINGS MASSACRED THE

CONGREGATION IN T H E

CATHEDRAL OF LUNA.

B A C K F R O M T H E D E A D

Once safe on his ship, Hastein climbed off his "sickbed" to put in action the

next step of his scheme. After nightfall, his messenger called on the count and

the bishop bearing the sad news that Hastein had died. On his deathbed he

asked for one more favor—that the bishop offer his funeral Mass and then

bury him in the cathedral monastery. Without a moment's hesitation, the

bishop agreed and set a time for the funeral the next day.

Meanwhile, the story of the bloodthirsty Viking who had converted on

his deathbed and now would be buried in the cathedral had spread to every

household in the city. The next morning, a grave procession of fifty Vikings,

each dressed in long, dark-colored robes, passed slowly into the city bearing

Hastein's corpse on a bier. Lining the streets the entire way from the gates to

the cathedral door stood the entire throngs of onlookers.

On the broad steps of the cathedral stood the bishop robed in elaborate

black vestments, his golden crosier clasped in his left hand. Beside him was the

count, and all around them stood a large number of priests and monks, as well

as a crowd of altar boys, each one bearing a tall, lighted candle.

After blessing the corpse with holy water, the bishop led the grieving

band of Vikings, along with a large crowd of curious townspeople, into the

cathedral. Inside the crowd filled the nave, the monks filed into the choir,

and the priests and altar took their places in the sanctuary. When the

funeral Mass was over, the bishop gestured to the Vikings to follow him to

the burial place.

Suddenly Hastein leapt off his bier, drew his sword, and before anyone

in the church could react, killed the bishop. Turning on the count, who was

HASTEIN KNEW

ROME LAY NEAR THE

TYRRHENIAN SEA

ON T H E WESTERN

COAST OF ITALY, BUT

HE MISTOOK LUNA FOR

THE ETERNAL CITY.

too astonished to defend himself, Hastein killed him, too. As several of

Hastein's men ran down the nave to bar the church doors, the rest of the

Vikings threw off their mourning robes, pulled out their weapons, and

attacked the defenseless congregation. In the bloody free-for-all that

followed, the Vikings spared only a few young men and women who would

fetch a good price at the slave market.

There must have been some prearranged signal, perhaps the tolling of

the bell at the conclusion of the funeral, because as the fifty Viking

"mourners" spilled out of the cathedral, their nearly 2,000 comrades leapt

off their ships and charged into the city. For the rest of the day they killed

and looted and took prisoners. When they had filled their ships with as

many captives and as much loot as the boats could hold, the Vikings set fire

to Luna and sailed away.

The sack of Luna had been a brilliant success except in one respect—the

Vikings had attacked the wrong city. Somewhere during their adventures they

had heard Christians speak of Rome as a great city of white marble buildings

where every church and monastery held a fortune in gold and silver and

precious jewels.

No Viking had ever plundered Rome, but Hastein and Bjorn intended to

be the first. They knew Rome lay in the country of Italy near the coast of the

Tyrrhenian Sea, but they had no directions more specific than that. When they

entered the Gulf of Spezia on Italy's western shore and saw a lovely city of

white marble churches behind high defensive walls, they assumed the town

must be Rome, and poor Luna's fate was sealed.

V I K I N G S O N T H E R I V I E R A

"Blue men!" the slave trader bellowed. "Black Men!" A fascinated crowd of

Vikings and Irish gathered around the auction block, staring at the strange

men up for sale, fresh off a Viking ship from the Mediterranean. It was a late

summer day in one of the port towns the Vikings had founded on the Irish

coast, but compared to their homeland near the equator, the Africans must

have found this strange island cold and damp. While the Africans shivered

and the Irish stared, the auctioneer began taking bids from eager Viking

buyers.

The "blue men" were probably tattooed Tuaregs, members of the Berber

ethnic group found in modern-day Libya and Algeria. The "black men" were

probably sub-Saharan Africans and may already have been slaves of the Moors

of North Africa when the Vikings captured them.

THE TUAREGS WERE THE

"BLUE MEN" OF MODERNDAY

NORTH AFRICA WHOM

THE VIKINGS CAPTURED

DURING THEIR TRAVELS

THROUGH THE

MEDITERRANEAN AND

SOLD IN IRELAND.

In the summer of 859, Bjorn and Hastein led their fleet of sixty-two

ships up the Guadalquivir River to Seville, hoping to have better luck than

the first Viking raiders. In fact, they did much worse. The Moorish garrison

defended their city with primitive flamethrowers that used a simple hand

pump to spew burning naphtha that consumed ships and roasted men. After

a disorderly retreat down the river, Bjorn and Hastein retaliated by plundering

and burning the towns Algeciras and Cabo Tres Forcas in the

province of Cadiz. Next they sailed to North Africa, where they seized their

exotic slaves. Which North African towns they attacked or what success they

enjoyed, aside from the captives, is unknown.

With winter coming, the Vikings made a seasonal camp in the south of

France. The weather was still good, so they attacked Nimes, Aries, and

Valence. When the Franks sent an army against them the Vikings retreated to

a new location—the Cote dAzur on the French Riviera—from which they

sacked the town of Pisa in Italy. It may have been from captured Pisans that

the two Viking chiefs first heard of Rome.

For two years, the Viking fleet ricocheted around the Mediterranean,

from southern Europe to northern Africa and back again. Hastein and Bjorn

may even have attempted an assault on Alexandria in Egypt—there are

rumors of such an attack, but nothing definitive in the records from the

period. By 861, Bjorn and Hastein were ready to return home. As they drew

close to the Strait of Gibraltar, they found their way blocked by a Moorish

fleet. The Moors had never had a navy before, but after the last attack on

Seville they built one specifically to crush the famous seafarers. The Vikings

had generations of experience in naval warfare, but the Moors trumped it

with their flamethrowers. Of the approximately sixty ships Bjorn and

Hastein took into battle, only twenty managed to fight their way through to

the Atlantic.

The Moors had adopted the flamethrower after the Byzantines had used it

on them a century or so earlier. It was a heavy metal tube with a hand-operated

pump. It operated just like the modern-day water cannons children play with

in the summer. The tube was filled with a flammable chemical and then, by

employing the pump, spewed liquid fire on one's enemies. Like the Byzantines,

the Moors had found that the flamethrower was especially effective when used

against enemy ships, as they were built of wood and caulked with pitch. At the

first spurt of flaming liquid a wooden ship would burst into flame.

T H E M O O R I S H C O N Q U E S T O F S P A I N

SPANISH AND

PORTUGUESE ARIANS,

CATHOLICS, AND JEWS

ALL FELL V I C T IM TO

THE MOORS AS THEY

CONQUERED THE

IBERIAN PENINSULA.

Islam gave the Arabs what they had

never had before—a cohesive idea,

bigger than any tribe or clan, around

which all the tribes and clans could rally.

Once they had been poor desert

wanderers; now they were the chosen

people of God. The truth of this

statement was confirmed by the Prophet

Muhammed, whose successful wars

against his opponents convinced the

Arabs that if they united against a

common foe, they were virtually

unstoppable.

After the death of Muhammed in

632, the Arabs found themselves in an

interesting political situation. The two

greatest empires in the region, the

Persian and the Byzantine, had just

finished a prolonged, destructive war

that left both sides exhausted.

Recognizing an opportunity to expand

their power and their new religion, the

Arabs swept down upon Persia, Syria,

and Egypt. Worn out by their last war,

the inhabitants barely put up a fight: The

greatest lands in the Near East fell into

the Arabs' laps. Then from Egypt the

Arabs moved westward, conquering

about half of North Africa.

In the year 710, Wittiza, the king of

Spain, died. Wittiza had belonged to the

Arian Christian sect, which the Catholic

establishment viewed as heretical.

Unwilling to see another Arian on the

throne, the Catholic bishops of Spain, in

a hastily organized ceremony, crowned a

Catholic nobleman named Roderic king.

Wittiza's outraged relatives fled to

North Africa to seek the protection of a

Spanish Arian count named Julian, who

ruled the region around present-day

Ceuta in Morocco. To drive out Roderic

and install an Arian king in Spain, Julian

invited or perhaps hired to fight for him

an army of Muslim Moroccans—Moorsled

by a general named Tariq ibn Zayid.

Julian even offered his own ships to

ferry the Moors across the Strait of

Gibraltar to Spain.

With Julian serving as his guide,

showing him the best harbors, the richest

towns, and all the other secrets of Spain,

Tariq enjoyed the kind of advantage that

rarely comes to an invader. There was

one other advantage that Count Julian

overlooked but that Tariq saw at once:

Spain was a divided nation. Catholics

and Arians were at each other's throats,

and even within King Roderic's own

family there were relatives who felt

they deserved to be king. On July 19,

W711, at the Battle of Guadalete at the

southernmost tip of Spain, Tariq's

Moorish army defeated and virtually

massacred Roderic's army. Roderic

probably died in the carnage, but his

body was never recovered.

Encouraged by news of such a

promising beginning, the Moorish

governor of North Africa sent

reinforcements to Tariq. Capitalizing on

the dissension in the country and the

treachery of the Spanish, as well as on

the Muslims' own sense of invincibility,

Tariq conquered all of Spain and Portugal

within five years. The only holdout was

the Christian kingdom of Asturias in the

northwest corner of the country.

After Hastein and Bjorn's near escape from the Moorish fleet, the

Vikings steered away from the Mediterranean but continued to raid the

Atlantic coast of Spain. In the late 960s, the Vikings sacked eighteen cities

in the little Christian kingdom of Asturias on the Bay of Biscay. They

captured the town of Santiago de Compostela, looted the shrine of St.

James, killed the bishop Sisenand, and finding the country to their liking,

decided to stay. For three years the Vikings occupied Galicia, living off the

local population, and sometimes taking captives to sell as slaves, until in

971 a Galician count, Gonsalvo Sancho, raised an army and drove the

Norsemen out.

The Vikings settled extensively throughout northern Europe, but they

found no place for themselves in the Mediterranean—with one exception, the

city of Constantinople. These Vikings, however, did not come to the great

city through the Strait of Gibraltar; they traveled south on the rivers of Russia

and the Ukraine to the Black Sea, where Byzantine generals recruited them to

serve the emperor as mercenaries. The Byzantines liked to think of themselves

as the heirs of the old Roman Empire, and in this respect at least they were

imitating the caesars who had used barbarian warriors to buttress the strength

of Rome's legions.

Contact between the Byzantines and the Vikings who had settled in and

around Kiev must have begun no later than the early ninth century, because

we know that in 839 Emperor Theophilus persuaded Viking chiefs, or "Rhos,"

as he called them, to let him hire some of their fighting men. Communication

between the Vikings in the Ukraine and the Byzantines became more frequent

after Olga, Princess of Kiev, and then her grandson, Vladimir, converted to

Christianity.

T H E V A R A N G I A N G U A R D

By the late tenth century, there was a large Viking detachment serving in the

Byzantine army—at least 6,000 men, each of whom had sworn a personal oath

to fight in defense of the emperor. They were called the Varangian Guard,

Varangian coming from two Old Norse words that mean "to swear an oath."

When Emperor Basil II attacked the rebel general Bardas Phocas, he

brought the entire Varangian Guard with him. In the final battle, as Phocas's

soldiers ran from the battlefield, the Varangians chased them down and, as one

Byzantine chronicler put, "cheerfully hacked them to pieces." After that day,

Basil made the Varangians his personal bodyguard—a function the Varangians

performed for succeeding generations of Byzantine emperors.

Eventually, the Varangian Vikings converted to Christianity and adopted

Greek as their first language. But they clung to some of their traditions. They

had a preference for using axes in battle and a weakness for heavy drinking—

although in Constantinople they drank wine rather than mead or ale. Their

drunkenness was so conspicuous that when King Eric the Good of Denmark

made a state visit to the Byzantine court in 1103, he delivered a speech to the

Varangians, saying they were giving their countrymen a bad name and urging

them to moderate their drinking.

There was one more thing the Varangians remembered—the runic

alphabet of their homeland. Rune graffiti has been found on columns and

other monuments in Constantinople (present-day Istanbul), as well as on a

pair of marble lions that were once in Athens but are now displayed in Venice.

In 1204, when the men of the Fourth Crusade were persuaded to sack

Constantinople rather than march to the Holy Land to liberate Jerusalem, the

only section of the city that was not overrun by the Crusaders was the part

defended by the Varangians. After that final victory, the Varangians disappear

from the historical record. In the entire Mediterranean world, Constantinople

was the only place where Vikings made a lasting impact.